This article first appeared on www.japansubculture.com. Permalink.

BY SARAH NOORBAKHSH | 20 MAY 2010

Learning Japanese business culture is always a hot topic for those looking to deal on this side of the Pacific, but little do many know that Japanese young adults are almost just as confused by the the traditions and hype surrounding the complex world of Japanese shafuu.

In Japan, corporate culture amongst established companies is not something that is organically developed or that reads from the pages of a self help book. Traditionally there have been two kinds of companies: 体育会系 (taiikukai-kei, sports-oriented) and 文化系 (bunka-kei, liberal arts-ish). From the definition it’s likely easy to grasp the general concept, and while bunka kei companies are more desirable for those calm, artsy types who enjoy having a life outside or work, taiikukai-kei are renowned for providing the motivated with high-energy, aggressive environments in which they can shoot for the stars–but often not, because unlike Western companies, until recently most traditional taiikukai-kei companies feature lifetime employment systems, 年功序列 (nenko joretsu, seniority by length of service) and all those other ultra-Japanese business practices that have gradually become archaic. Taiikukai-kei here) companies are also renowned for they way they treat employees, going beyond the typical forced overtime and into the realms of abusive language and behavior to subordinates and even reports of regulated haircuts for new hires. (Read more about company culture and how it’s begun to affect young people.

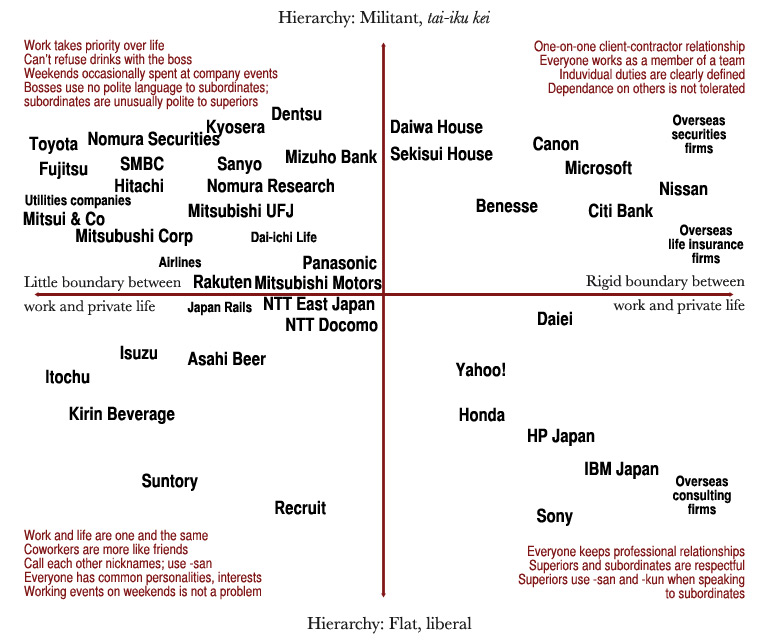

For May, perhaps to give April’s new hires a belated heads up that they may have made a bad decision, magazine Zaiten has a special feature on “Real Job Hunting,” featuring a fantastic chart, translated below:

The chart lays out in four neat areas some of the country’s most well-known firms, as well as particular industries that are popular destinations for Japanese graduates.

Before we get into the chart, Zaiten has this to say about company culture in Japan. There are roughly six ways to group companies: cultish charisma-kei (カリスマ系), family-run dozoku-kei (同族系), strict infura-kei (インフラ系), foreign gaishi-kei (外資系), authoritarian chuoshuken-kei (中央集権系) and heavy industries-basedjukochodai sangyo-kei (重厚長大産業系). Whew. Charisma-kei and dozoku-keicompanies are similar in style, they say, in that both types put the company founder or president on a kind of pedistal, decorating offices and board rooms with his photo and adhering strictly to the guidelines these founding fathers have set down. The company goes through efforts to “brainwash” new hires, lest they get sick of kowtowing and quit.

One company Zaiten cites as being the epitome of charisma-kei is manufacturer Kyosera, which half-forces employees to purchase books written by founder Kazuo Inamori on the “Kyosera philosophy.” Dozoku-kei companies like Lotte or the massive Takenaka Corporation have employees stand up and sing the company song every morning. The Yamazaki Baking corporation prides themselves on using the same recipe for their fluffy white bread as was used by the founding Iijima family–which contains carcinogenic potassium bromate despite the fact that it is banned in most of the world and other major Japanese producers have ceased its use. The article say that many of these companies are less about making extremely high profits than they are about preserving tradition, making them unsuitable for those who are aggressive and looking to succeed.

Gaishi-kei companies are easily recognizable as overseas firms in the Japanese marketplace. These performance-based workplaces are the antithesis of Japan’s lifetime employment (終身雇用 – shushin koyo) but share the same “top-down” hirearchtical traits of Japanese companies as, the article points out, superiors plainly downsize workers if the need arises. As a bonus, however, the world of service zangyo, or unpaid overtime, is almost unheard of.

Some of Japan’s biggest giants, at least those closest to the government, have aninfura-kei culture. Typically transportation or utilities companies such as Japan Railways, Tokyo Gas or NTT, these groups unusual in that they often have little or no competition–making sales and work performance obsolete–and divide their employees up into career and non-career workers. Perhaps some of the most typical Japanese companies, seniority is decided by length of service and company hierarchy is ultimately respected. The article says that, according to one career-track NTT employee, promotions are decided by how well you get on with your boss and how neatly your documents are written. The company attitude towards those on a non-career employees follows that of taiikukai-kei, with reports of ground staff at ANA “being scolded until they cry” after having made mistakes.

In chuoshuken-kei companies, those overly focused on a particular part of their business, most typically R&D of a certain product, will pour much effort into particular departments while neglecting those in other divisions. The phenomenon can be seen in companies ranging from residential property developers to food makers, or any company where one portion of employees are skilled in the firm’s main business while the rest are not. Those who are not skilled are promised by their employer a chance to pursue a career on the production side of the business if only they first experience life “on the front lines.” Zaiten warns that this terminology typically means a new employee may be banished to an unpopular regional area to “gain experience” for the majority of their career with little opportunity to gain skills in a more desired field.

The article advises that, to a certain extent, looking at the business cycle of a company, from the beginning of a project to the end, is a good measure of what kind of company culture it will have. Age determines seniority in those companies with long business cycles, such as ones involved in the aerospace industry or nuclear power, because of the time it takes to experience work throughout the life of a project. On the other hand, IT companies that do systems integrations or install information systems have a relatively short business cycle and offer opportunities for younger employees to be more influential, making for a more level working environment.

Regardless of the type of company, a job hunter can generally determine where a potential employer falls on the chart above with two essential questions: “What happens if someone doesn’t make sales?” and “Does your department tend to go out drinking together a lot?”

If someone doesn’t hit their expected target at Nomura Securities, for example, bosses hound the employee, forcing him to try harder or admit defeat. Says one employee, “They’re really into seishin-ron (精神論 – mental training against adversity) here, and this is a place where ‘I couldn’t make quota’ just doesn’t cut it.” At Daiwa Securities, on the other hand, the atmosphere is more encouraging: “If someone says they can’t hit their sales mark, most bosses will reply with a ‘Well, let’s just try harder tomorrow!’ kind of thing,” explains a worker. Out of around 3,000 sales employees at the company in 2008, 1,068 had won the “President’s Award.”

Company drinking parties are a classic Japanese institution that are enjoyed by some yet grudgingly joined by most. Those companies that tend to encourage obligatory extracurricular activities, in this most traditional sense, are known as being “wet”–clingy and overly involved in employee’s lives. Today, along with the gaishi-kei group, a number of domestic ventures, start-ups, SMEs and even divisions in some major companies, employ a more “dry” type of management, with lines firmly drawn between professional and private.

So what about the chart? After analyzing various types of company culture, Zaiten organized the information on two axis (wet vs. dry and flat vs. hierarchical), creating four zones. Overseas companies tend to stray toward the right side, with firm boundaries between public and private, while the Japanese companies still uphold the “my job is my life” status quo on the left side (and most happen occupy the upper left corner, where the corporation takes up all employee’s time and beats them down for it).

Interesting to note are the companies with a “flat” structure in the lower regions of the chart. An IT company would be ideal for someone who wants to leave the office at 6pm and have a friendly relationship with their boss–something we tend to find normal in the West. For the right person, however, one of the companies on the lower right might not be a bad choice; is it coincidence that top beverage makers (read: beer) like Suntory and Kirin have more casual workplaces where people tend to spend a lot of time?

Zaiten advises job hunters: The days of being sheltered by your employer are over, and new hires have to realize the importance of maintaining a network outside of their company. Before taking a job, think carefully about whether you want to turn into a salaryman who lets drinking with the boss take up all of his time.

As a bonus for those who made it all the way to the bottom, here is a post from the guys at Mutantfrog Travelogue about Gyoza no Ohsho, a ramen restaurant with some unusually taiikukai-kei training for new employees.

Brilliant